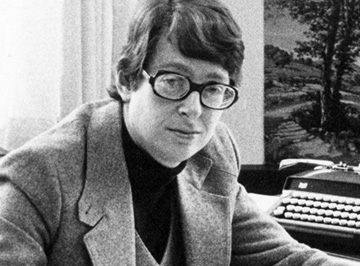

About Nancy L. Schwartz

A dedicated scholar and teacher, Nancy Schwartz was the Morrison Professor of Decision Sciences, the Kellogg School's first woman faculty member appointed to an endowed chair. She joined Kellogg in 1970, chaired the Department of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences, and served as director of the school's doctoral program until her death in 1981. Unwavering in her dedication to academic excellence, she published more than 40 papers and co-authored two books. At the time of her death she was associate editor of Econometrica, on the board of editors of the American Economic Review, and on the governing councils of the American Economic Association and the Institute of Management Sciences.

The Nancy L. Schwartz Memorial Lecture series was established by her family, colleagues, and friends to her memory. The lectures present issues of fundamental importance in current economic theory.

Morton I. Kamien on Nancy L. Schwartz

This text was taken from Frontiers of Research in Economic Theory: The Nancy L. Schwartz Memorial Lectures, 1983-1997

Nancy Lou Schwartz began her academic career in 1964 at Carnegie Mellon University’s Graduate School of Industrial Administration. She was part of the wave of young faculty that Dick Cyert, the school's dean, hired between 1963 and 1965. They included Tren Dolbear, Mel Hinich, Bob Kaplan, Lester Lave, John Ledyard, Mike Lovell, Bob Lucas, Ken MacCrimmon, Tim McGuire, Dick Roll, and Tom Sargent. By the time she left Carnegie-Mellon in 1970 for Northwestern University she was a tenured associate professor and had been awarded a Ford Foundation Faculty Research Fellowship.

Nancy had come to Carnegie-Mellon fresh out of Purdue University’s fabled economics department. Ed Ames, Lance Davis, George Horwich, Chuck Howe, John Hughes, Jim Quirk, Stan Reiter, Nate Rosenberg, Rubin Saposnik, and Vernon Smith were among her teachers, while Pat Henderschott, Tom Muench, Don Rice, Gene Silberberg, and Hugo Sonnenschein were among her classmates. Her Ph.D. dissertation, supervised by Chuck Howe and Stan Reiter, dealt with the optimal scheduling of towboats and barges along a river with multiple branches. It involved a generalization of the standard transportation problem in which a single conveyance is employed to haul cargo to two complementary conveyances. The optimal coordination of the two conveyances adds a layer of computational complexity to this transportation problem. Nancy developed a simulation routine to approximate its optimal solution.

Nancy was a first-rate graduate student by all the conventional measures, such as grades, passing of qualifying examinations, and timely writing of a dissertation. The outstanding characteristic for which she was known to her teachers and classmates was an uncanny ability to spot logical flaws in an argument. And the manner in which she would point out the flaw was also special in that it always came in the way of a seemingly innocent clarifying question. Nancy was too shy and too polite to point out a flaw directly. However, in time, her instructors and classmates came to realize that when she claimed not to understand a step in an argument, typically a critical one, it meant almost certainly that it was wrong. All this, of course, created a certain amount of dread among the instructors when her hand went up to ask a question, and some merriment among her classmates.

When Nancy joined Northwestern's graduate school of management in 1970 as a full professor, after considerable coaxing by John Hughes and Stan Reiter, it was hardly the world-class institution it eventually came to be. The physical facilities were abysmal. There was no dedicated management school building on the Evanston campus, and the bulk of the masters program teaching was on the Chicago campus, Office space consisted of wooden partitions in the old library building that did not reach the ceiling. The Department of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences, MEDS, did not yet exist. Its predecessor was a combination of three departments: Managerial Economics, Quantitative Methods, and Operations Management. There were a few bright young faculty already there, including Dave Baron, Rich Khilstrom, Mark Walker, Tony Camacho, and Matt Tuite, but there remained a lot to be done. And so Nancy became one of the three senior faculty members instrumental in building the department. She participated in the hiring of John Roberts, Mark Satterthwaite, Arik Tamir, Ted Groves, Bala Balachandran, Roger Myerson, Ehud Kalai, Eitan Zemel, Bob Weber, Nancy Stokey, Paul Milgrom, Bengt Holmstrom, Yair Tauman, and Dov Samet.

Nancy headed up the department's Ph.D. program and chaired the department from 1977 to 1979 and then became the director of the entire school's Ph.D. program. She was involved in guiding numerous students through their Ph.D. dissertations, including Raffi Amit, Raymond DeBondt, Eitan Muller, Jennifer Reinganum, and Esther Gal-Or. In addition to attending to these internal administrative responsibilities, Nancy served on the Council of the institute of Management Sciences, on the editorial board of American Economic Review, and as an associate editor of Econometrica. In 1981 Don Jacobs appointed her the Morrison Professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences. She was the first woman to hold a chaired professorship at the school of management.

Nancy's research beyond her dissertation was focused on theoretical issues in industrial organization. The earliest was inspired by J. R. Hicks's theory of induced technical advance, in which he claimed that firms directed their research efforts toward reducing the employment of a relatively more expensive factor of production. This theory was criticized on two grounds. The first was that it ignored the relative costs of achieving each type of technical advance. The second was that it was more relative factor shares than relative factor prices that induced the direction of technical advance.

Nancy was involved in a series of papers that dealt with all these issues through the analysis of the behavior of a firm seeking to maximize profits over time by choosing both the levels of its factors of production and the focus of its research efforts, taking all costs into account. The analyses suggested that both relative factor prices and relative factor shares played a role in inducing the direction of technical advance. in the long run, technical advance tended toward neutrality; no one factor was targeted for reduction relative to the others.

Nancy's next major research project dealt with how rapidly firms developed new products or methods of production in the presence of rivals. This work eventually led to the theory of patent races. It was inspired by Yoram Barzel's claim that the quest to be the first to innovate led firms to overinvest in research and development from society's standpoint. This claim appeared to challenge the conventional wisdom that firms tended to underinvest in research and development from society's standpoint because they could not capture all the benefits, Barzel's result was driven by the assumption that the winner of the race to innovate would capture all the realizable profits and that the quest to edge out rivals would force the firm to accelerate development to the zero profit point. This would lead to higher than optimal investment in research and development in which the marginal cost of advancing development only slightly equals the marginal benefit of earlier access to the profit stream. Barzel supposed that each innovator knew who the rivals were. The critical feature of the work in which Nancy was involved was the opposite assumption, namely, that the innovator did not know at all who the rivals were. However, the innovator knew that they were out there and took account of them through the hazard rate, the conditional probability of a rival's introduction of a similar invention at the next instant of time given that it had not yet been introduced. In this model the innovating firm faced a sea of anonymous rivals, any one of whom might introduce a similar invention in the very next instant of time. The large number of rivals assumption meant that the individual firm's level of expenditure on research and development did not elicit an expenditure reaction from its unknown rivals, to whom it, too, was unknown, Rival imitation was allowed in this model and it was shown that when it was immediate, investment in research and development would cease in conformity with the conventional wisdom. Moreover, increasing intensity of competition in the form of a higher hazard rate could not force a firm to accelerate development of its innovation to the break-even point, as the decline in the probability of winning would cause firms to drop out of the race short of it. Thus, the model allowed for increases in a firm's research and development expenditure with increasing intensity of rivalry up to a certain point and a decline thereafter, a feature consistent with empirical findings that industries in which the intensity of competition is intermediate between monopoly and perfect competition are the ones with the most research intensity. It was precisely this feature of the model that led to Loury's first formal patent race paper, in which the hazard rate became endogenously determined by Cournot-type interactions among the rival firms through their research expenditures. Lee and Wilde's paper followed, then the Dasgupta and Stiglitz, papers, and then Reinganum's fully dynamic patent race model.

The works on the timing of innovations in the presence of rivals naturally led to the question of how a successful innovator might adopt a price strategy to retard rival entry and to the next major project in which Nancy was involved. The major theories of entry retardation at that time were the limit pricing ones proposed by Bain and by Sylos-Labini, as synthesized by Modigliani.The crux of this theory is that the incumbent firm sets a price and supplies the corresponding quantity demanded so that the residual demand function faced by the potential entrant just allows him or her to realize no more than a normal profit. Implementation of this limit pricing strategy requires that the incumbent know the average cost function of each potential entrant. The project in which Nancy participated involved dropping this assumption and replacing it with the supposition that the conditional probability of entry given that no entry had yet occurred, the hazard rate, was a monotonically increasing function of the incumbent's current market price. This assumption led to the formulation of the incumbent firm's problem as an optimal control problem with the probability of entry on or before the present time the state variable and the current price the control variable. The firm's objective was to maximize the present value of expected profits, where its preentry profits are at least as high as its post-entry profits, which are determined by whatever market structure emerges after entry. It was implicitly assumed that by lowering its price, the firm sought to divert a potential entrant to entry into another industry. The analysis of this model disclosed that the incumbent firm optimally chose a price below its immediate monopoly price but above the price it would take to deter entry altogether. In other words, it is optimal for the firm to delay entry rather than postpone it indefinitely. It is in this sense that the incumbent firm engages in limit pricing.

This model of limit pricing under uncertainty eventually led to Esther Gal-Or's dissertation and the Milgrom-Roberts paper in which the incumbent firm's current price is used to signal a potential entrant about the type of competitor he or she will face after entry. Its original vision as a game among incumbents seeking to divert entrants away from themselves was realized in Bagwell's work.

Beyond these major projects, Nancy was involved in a number of less prolonged excursions. There was a widely cited paper on the optimal maintenance and sale date of a machine Subject to an uncertain time of failure. There were analyses of a growth model involving an essential exhaustible resource and endogenous development of a technology to replace it; of whether competition leads firms to produce more durable products; of the effect of health maintenance organizations on the delivery of care services; of the consequences for a firm seeking to maximize profits over time by producing a durable good by means of labor and capital, of the irreversibility of capital investment, of a firm's adoption of new technology when it anticipates further improvements in technology; of the consequences of technical advance for international trade; of the consistency of conjectural variations; and of the role of exclusion costs on the provision of public goods.

Apart from the individual articles, Nancy coauthored two books: Dynamic Optimization: Calculus of variations and Optimal Control in Economics and Management Science and Market Structure and Innovation. The first was the outgrowth of an intense use of techniques for optimization over time in many of the analyses she conducted. The focus of the book was to expose to the student the tricks that were employed in the application of these techniques rather than provide a rigorous treatment of the theory behind them. The second was the culmination of all the work in technical advance in which Nancy had been involved. It was the direct result of a survey article on the same subject that she had coauthored.

Nancy led a full and successful academic life and interacted with many of the best economists in her cohort, the older generation of economists who were her teachers, and the younger generation that she taught or hired. She provided a role model for younger women who contemplated becoming academic economists. The fact that all but one of the distinguished contributors to this volume are male says all that needs to be said about the milieu in which she carved out a respected niche.

Nancy L. Schwartz